Sandhill crane pair dance sequence

Dec. 22,23: Two nights in Bluff on a trip through UtahUnder the direction of John Taylor, Silas S. Smith and Danish settler Jens Nielson led about 230 Mormons on an expedition to start a farming community in southeastern Utah. After forging about 200 miles (320 kilometers) of their own trail over difficult terrain, the settlers arrived on the site of Bluff in April 1880.[7] (The trail followed went over and down the "Hole in the Rock", which now opens into one of the tributaries of Lake Powell.) The town was named for the bluffs near the town site.[8] The town's population had declined to seventy by 1930[citation needed] but rebounded during a uranium prospecting boom in the 1950s.[7] With the uranium decline in the 1970s, Bluff again declined and now remains a small town with about 200 residents. [Wikipedia]

Bluff Fort Historic Site commemorates the original pioneer town founded by Mormon missionaries at the end of their expedition to settle the San Juan area in 1880. Featuring recreations of the town, complete with meetinghouse and cabins decked with some original furnishings provided by local families, Bluff Fort offers an interactive historical experience. Pioneer Houses, Bluff

Old Cars, Bluff

October 27,28; Grebes on Mono LakeA night by Mono lake for dark sky astrophotography, and an evening and morning by the lakeshore for bird photography. Mono Lake is a crucial fall staging ground for vast numbers of Eared Grebes,\. They gather by the hundreds of thousands (sometimes millions) to fattun up on brine shrimp and alkali flies from late summer through fall (July-November) before heading south to breeding grounds. Here they more than double their weight, and the sizes of their muscles and organs change. The pectoral (chest) muscles shrink to the point of flightlessness and the digestive organs grow significantly. Before departure for the wintering grounds, the process reverses; the digestive organs shrink back to about one-fourth their peak size, and the heart and pectoral muscles grow quickly to allow for flight.

October 12-17: Butterflies at the John C. Campbell Folk SchoolI had been signed up for a photography class at the Folk School, but this was cancelled. There were no other classes available that appealed to me, so I was looking for my own photographic project that would keep me profitably occupied for the week. Walking past the School gardens I noticed there were many butterflies flitting around the flowers...

Eleven species of butterflies around the Folk School gardens

More butterfly portraits

September 23-30; A roundtrip drive along highway 395 to visit family in Redding - with stops outbound and on the return to photograph fall colors in the Eastern Sierras.On the return journey colors were most prominent at lower elevations.McGee Creek Canyon

Convict Lake

Gull Lake

Silver Lake

|

Single backlit aspen leaf; E. Sierra Fall Colors 2025 |

Driving back along highway 120 from Sagehen to Mono Lake we found a group of maybe 50 wild mustangs from the Montgomery Pass herd grazing on a wide meadow.

A ReturnVisit to Obsidian Dome; August 2025

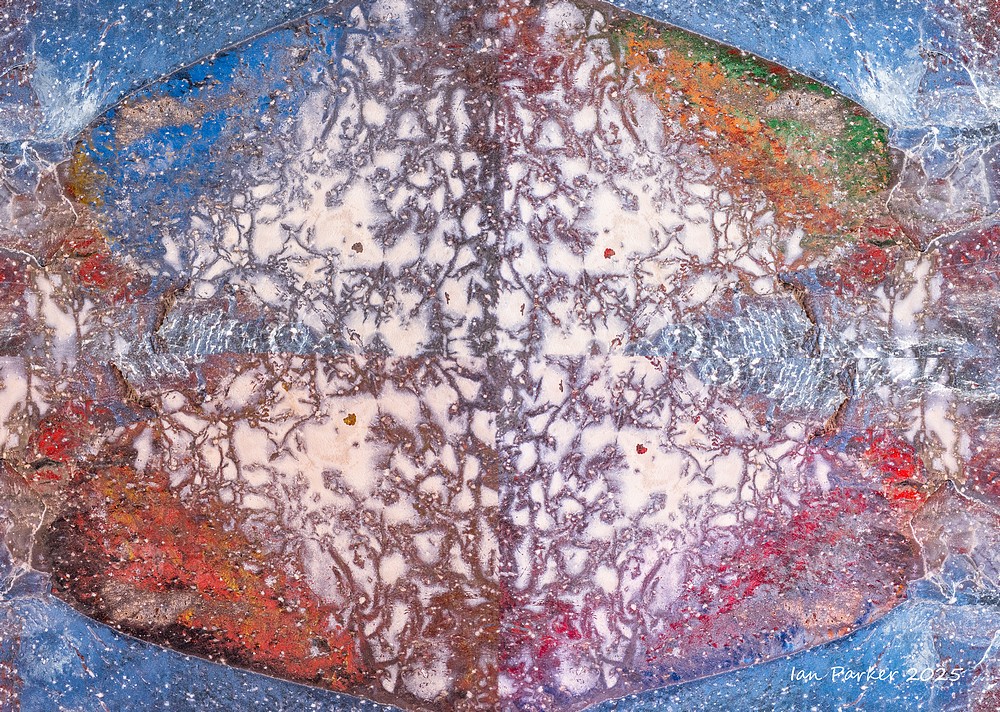

On a second visit to the Obsidian Dome I used a colorful deflated beach ball to generate a wider color palette of obsidian reflections.

From Fossil falls through Mazourka Canyon to Obsidian Dome; August 21-22, 2025

Fossil Falls

Weathered rocks and lichen on the summit of Mazourka Peak

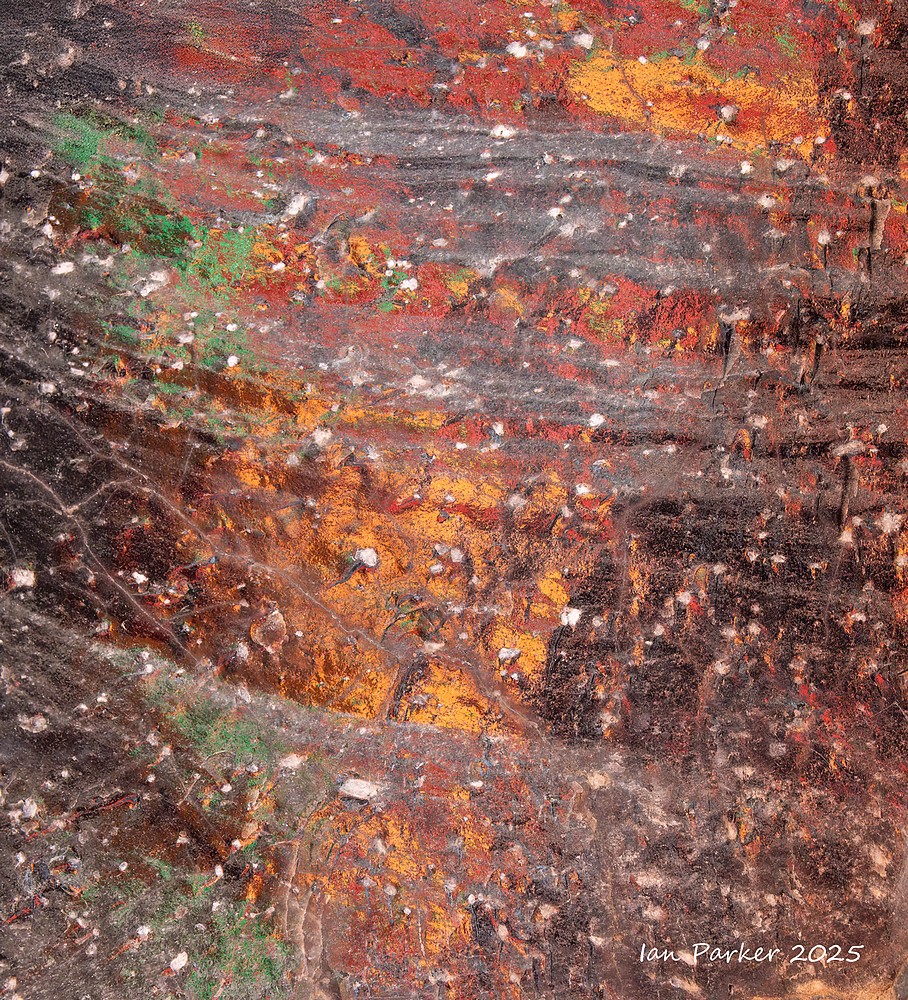

Obsidian Dome

Having acquired a new hobby of astrophotography, Anne and I have been taking regular excursions around the time of the new moon to dark sky locations far from the marine layer that obscures our view of the stars at home. The Mojave desert is a good place for reliable dark and clear skies, but in summer it gets forbiddingly hot once the sun has risen. Thus, we have been venturing further afield to higher and cooler elevations, driving up highway 395 through Owen’s valley toward Mono Lake. For astrophotography this area boasts Bortl1 skies, about as dark as it is possible to find in the lower 48 states. Moreover, the Mono basin holds many interesting locations for daytime landscape photography. One that I had not previously explored is marked by a highway sign a few miles south of Mono Lake pointing to a dirt road leading to Obsidian Dome.

The name “dome” conjures up an image of a rounded, compact dome of obsidian. However, arriving there we foundsomething rather different; tObsidian Dome is actually a 400ft high chaotic mass of volcanic rocks, created by eruptions as recently as 600 years ago, and extending over 5 square miles. The dirt road continues around the perimeter of the dome, where massive blocks of obsidian overhang the steep escarpment, from which large boulders have tumbled down to the forest floor. We parked at a shady clearing between the trees, and I wandered around the base of the dome. At first glance there did not seem to be much photographic promise,

But a closer look among the ankle-twisting jumble of rocks revealed hidden gems...

Unlike most rocks that take thousands (or even millions) of years to form, obsidian is created in the blink of a geological eye from lava that cooled so fast that it did not have time to form crystals. It is famous for its jet-black appearance but, despite its dark color, obsidian catches and reflects light in a way that adds depth and intrigue to its appearance. When polished, obsidian achieves a mirror-like finish, and polished obsidian stones (Scrying Mirrors} were used as divination tools by priests and shamans In Mesoamerican cultures for rituals communicating with spirits.

Even in their natural state many of the obsidian boulders at the base of the dome appeared polished and highly reflective, glinting brightly in the sunlight. The sun reflections were too bright and contrasty to photograph, so I crouched down and sought out polished areas on the shaded side of the boulders. There, the obsidian reflected the blue sky in wonderfully varied patterns, determined by the topography the glass surface as it cooled. Unexpectedly, I could also see patches of red interleaved among the blue! Fortuitously, I happened to be wearing a red T shirt that day which, catching the sunlight, threw a bright illumination on the obsidian. The interleaved patterns of red and blue reflections changed kaleidoscopically as I altered my viewpoint, and as I moved to reposition the light source from my T shirt.

The Aztecs believed that the reflections from obsidian mirrors had the power to reveal hidden truths, communicate with the spirit world, and foretell the future. While I don't believe that the images I show here posess such powers, it does seem that I may have stumbled on a unique new niche of abstract photography; Google searches have not pulled up similar images.

The area around Obsidian Dome has been well picked over by rockhounders, and I was not able to find any small pieces of obsidian among the large, immovable blocks. However, after a strenuous hike to a more remote location at the top of the Mono/Inyo craters I did find a fist-sized chunk of obsidian that evoked some beautiful faceted reflections.

Black Mirror

- Obsidian T shirt reflection #1

Volcanic Crater and Cinder Cone

Panum Crater, Mono Lake, August 2025

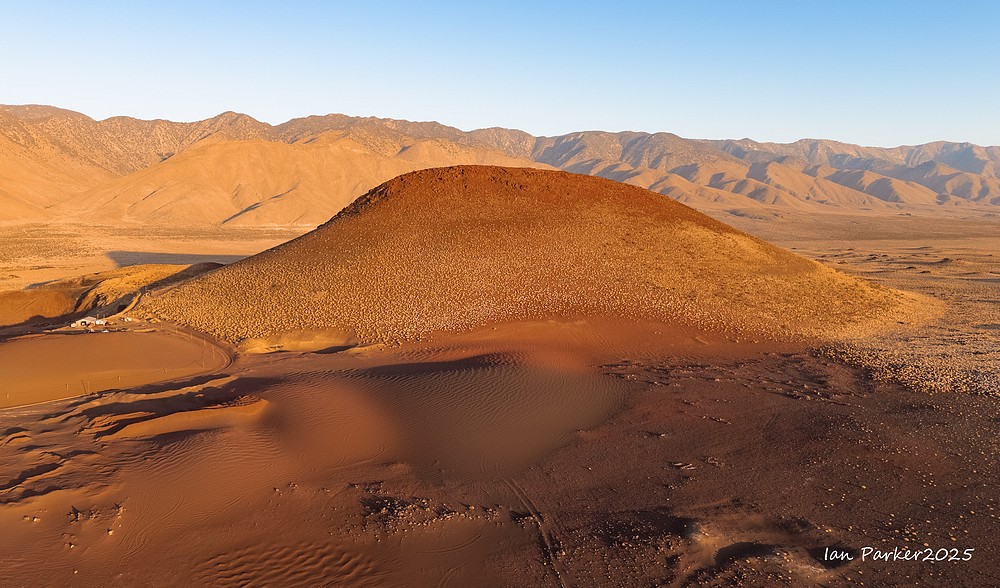

My new interest in astrophotography has taken us to visit dark sky sites, most recently to the area around Mono Lake. Looking for things to do and photograph in the daytime around the lake I discovered an unexpected new interest in things volcanic. Mono Lake is located at the north end of the Mono-Inyo Craters volcanic chain, a 25-mile-long series of volcanoes in eastern California that includes two volcanic islands in the lake, Paoha and Negit, as well as a cinder cone on its shore. This volcanic field is still considered active, and the most recent eruptions in the lake occurred only 400 years ago, forming the islands. The USGS monitors this area for potential future explosive activity. A well-trodden trail gives access into Panum Crater. A steep climb from the parking lot leads up to the rim, from where there are two alternative paths. One circumnavigates the rim, while the other drops down before climbing up to the central, jagged dome. However, neither really gives a good impression of the structure of the crater. You have to mentally piece together views from different sections of the trails to get an appreciation of how it would look from the air.

After taking this photo I estimated it would be about a half hour before sunrise, too long to keep the drone in the air without depleting the battery, so I brought it back home, changed to a fresh battery and waited to take off again until a few minutes before sunrise. This time I flew the drone over to the north side of Panum Crater, capturing the photo below while the light was still diffuse just before sunrise, looking across to the chain of the much larger Mono Craters.

Finally, as the sun’s rays first illuminated the crater, I swung the drone around to the east, to align it with the shadow cast toward the Sierra Nevada mountains. I have made a mental note to come back and shoot this scene in winter, when the Sierras are snow covered, and perhaps when snow may also enhance the topography of the crater. |

Cinder Cone (Red Hill), along Highway 395

Drone shots at sunrise.

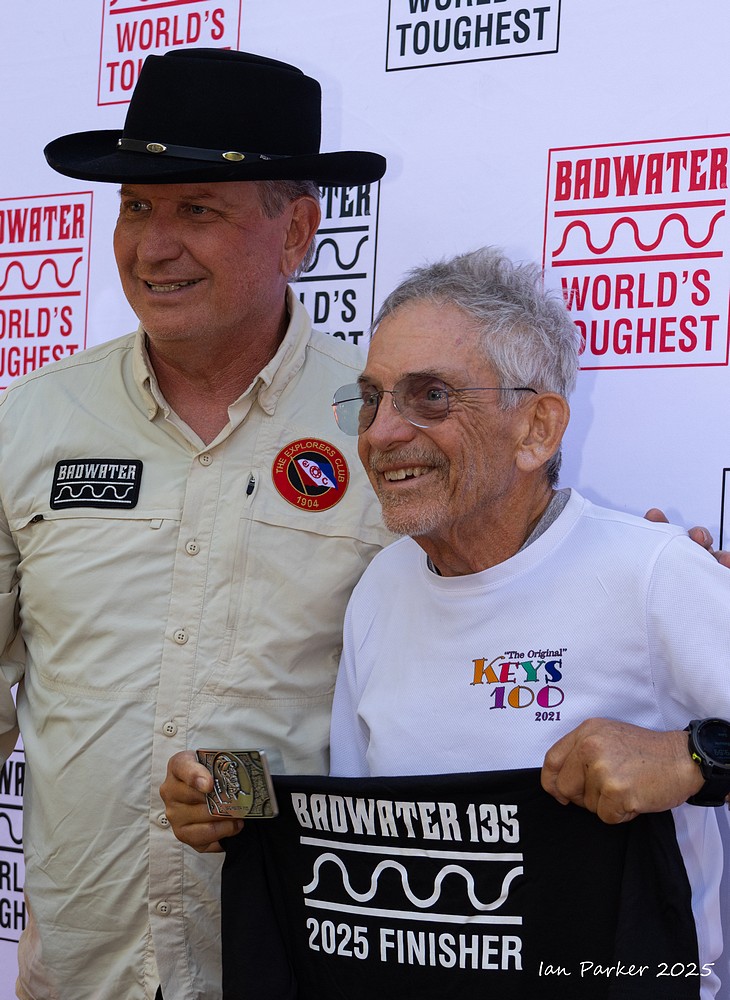

Badwater 135 Ultramarathon; : July 7-9th 2025

This was my 18th year at the Badwater Ultramarathon, the "World's toughest footrace"; eleven years as a runner or pacer, and six helping on the race staff and as a photographer. My approach the first year I came to photograph the race was from the perspective of a landscape photographer, aiming to place the runners in context of the spectacular scenery of Death Valley and the Eastern Sierras. This year I shifted gears, and also took on the mindset of a 'street'/portrait photographer, concentrating on the runners and their support crews. Badwater offers a photographic challenge of capturing the emotions of a group of very special people pushing themselves to the limit in an extreme environment. Moreover, the runners and their support crews are friendly, like having their pictures taken, and in any case have all signed waivers permitting the taking and publishing of photos!

The images below are a selection from many hundreds of shots. Click HERE for the race website which includes links to many ofther photos and full race results.

Start line at Badwater Basin for the 8:00pm wave

|

|

Start line at Badwater Basin for the 8:00pm wave

Morning, July 8: Climbing out of Death Valley over Towne Pass

|

The Oasis at mile 51

|

Descending Towne Pass into Panamint Valley

The climb out of Panamint Valley up to Father Crowley's Point

|

Leaving Death Valley National Park

Highway 136 along Owens Lake

Ascending the Portal Road

|

Finish line at Whitney Portal

|

|

The New Bentonite Hills, Hanksville, Utah - May 23,24

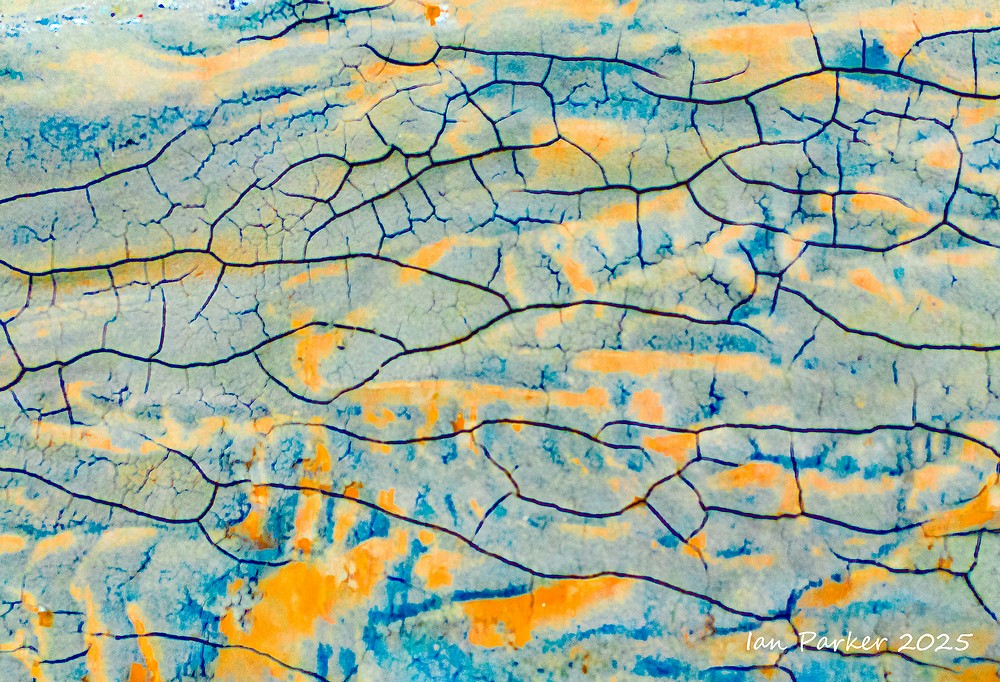

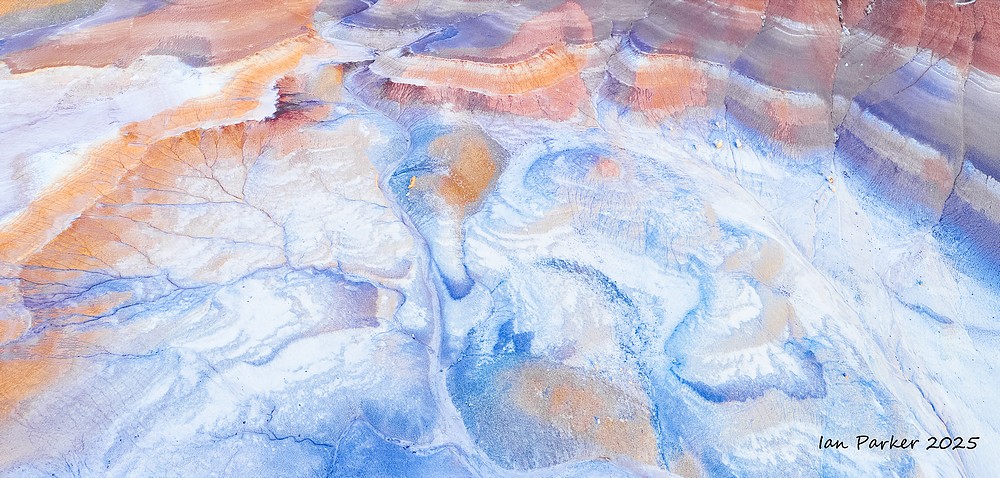

The Bentonite Hills in Utah are a unique geological formations, primarily composed of bentonite clay. This type of clay, known for its exceptional swelling properties and plasticity, gives the hills their distinct appearance and character. Formed from volcanic ash deposits undergoing weathering over millions of years, bentonite clay primarily consists of montmorillonite, along with other minerals like quartz, iron oxides, manganese and feldspar imparting their rich pigments to the soil and rock formations. Due to the diverse mineral composition the Bentonite Hills appear in colors, ranging from shades of red and orange to earthy browns, yellows and sometimes even blue - depending on the lighting and time of the day. The view is otherworldly…like something you might see on Mars Perhaps that’s why they built the Mars Desert Research Station” (MDRS) less than a mile away.

However, arriving in the middle of the day and stepping out of the car it was apparent that regular landscape photography approaches would not do a good job of capturing all this. One problem was that of perspective. The contorted ovals and concentric colored rings of the bentonite domes are not readily apparent from ground level. That had a ready solution, as I had brought my drone and the location is Federal land administered by the BLM (Bureau of Land Management), which allows the use of drones. A second problem was that the colors of the bentonite appeared rather brown and dull in full sunlight. The lighting at dawn and dusk gave an improvement, but I thought there was still more to be extracted.

My photos below thus show the results of applying progressively increasing levels of saturation to my drone shots. These do not depict false colors, or the hallucinations of AI, but reveal natural colors that are actually present, but are normally too subtle to be visible by eye.

Drainage Patterns

Abstracts

Other observations near the Bentonite Hills

Salton Sea Ultramarathon - April 26

Aselection of photos below. Click HERE for more.

|

Miles 2-6; Running through Salton City

Mile 6.5; The culvert under highway 86

Mile 8; A first sandstorm heading to Anza Borrego

Mile 10.5; Climbing the first hill

The microwave tower (mile 14, checkpoint #1) is a landmark visible for many miles along the course of the race

Miles 15-23; Through the desert

Mile 24; Another sandstorm at the turnoff to Font's Point

Mile 31; Approaching Borrego Springs

Mile 40; Hellhole Canyon - checkpoint #3

Miles 40-41; Setting out on the hiking and riding trail

Atmospheric phenomena while we detoured back to camp overnight in the warm, dry desert (while, the runners continued through the night at higher elevations in cold, wet and misty conditions.)

Mile 45; Culp Vally, checkpoint #4

Miles 70-81; Climbing in mist and rain up the East Grade Road to the finish atop Palomar Mountain

| IanParker 1146 McGaugh Hall University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 |

Please send enquiries to |

BACK TO > |