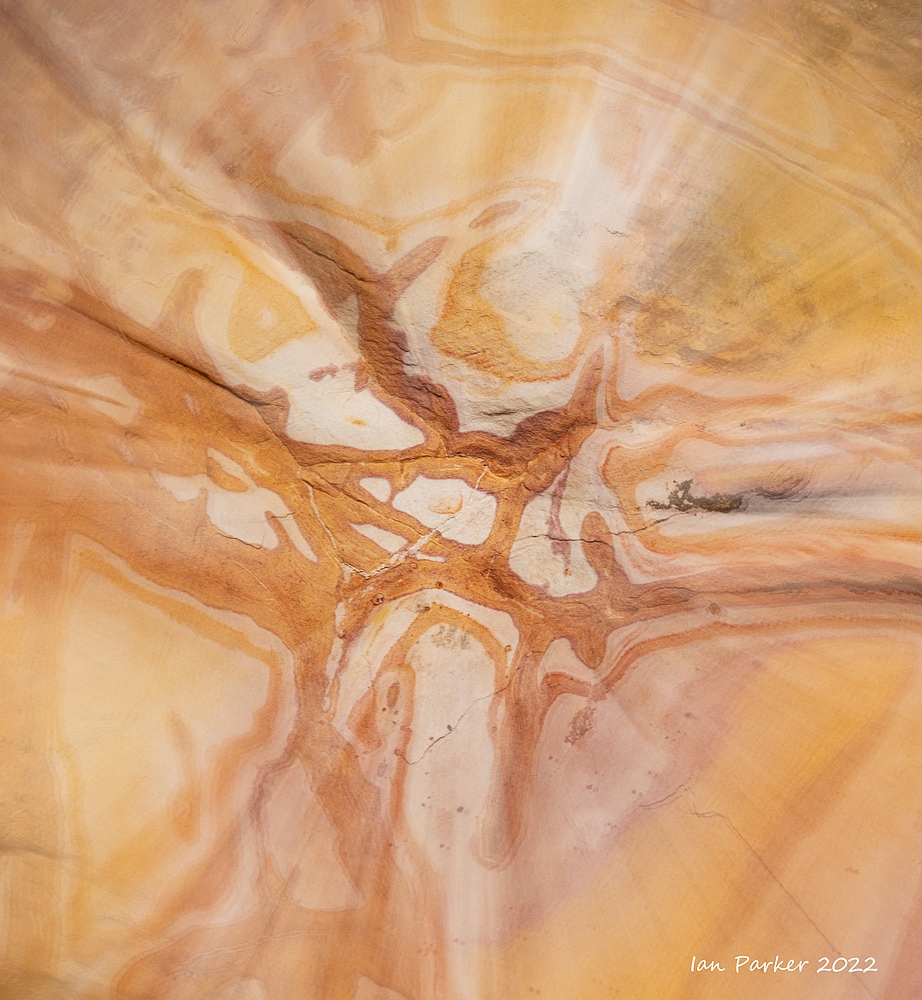

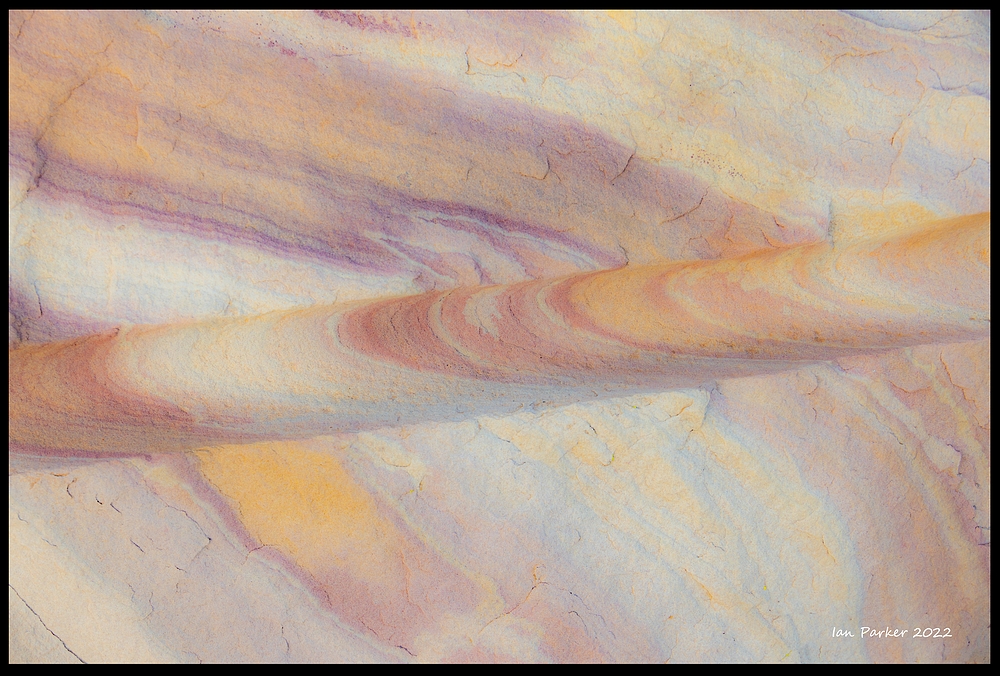

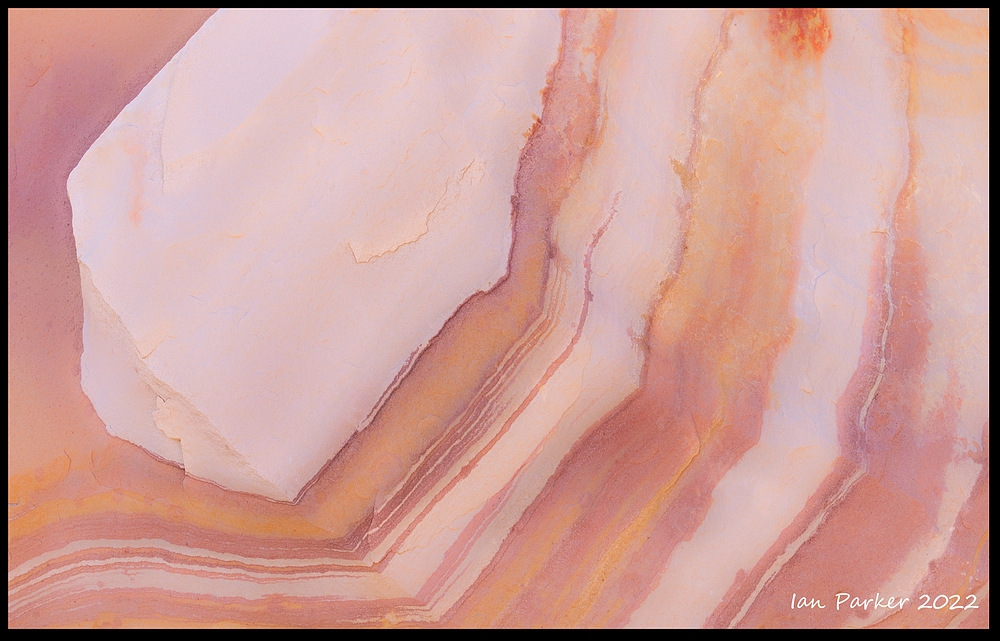

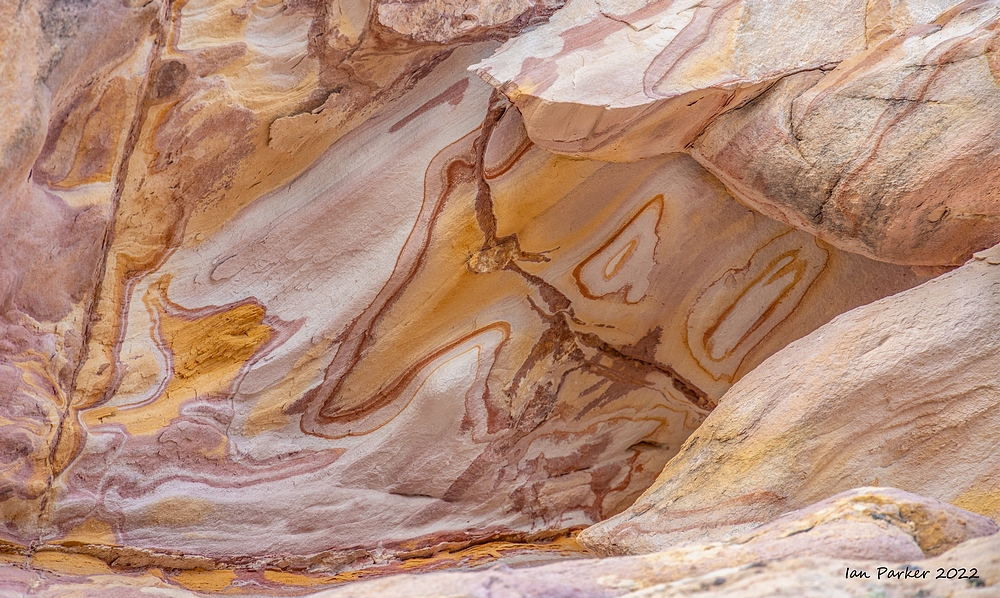

The Clay Cliffs of Omarama

|

Dec 4 - Dec 19

SUB-ANTARCTIC ISLANDS of NEW ZEALAND and AUSTRALIA

We voyaged to the remote sub-Antarctic islands of New Zealand and Australia on the "Birding Down Under" expedition organized by Heritage Expeditions. "Snares, Bounty, Antipodes, Auckland, Campbell, Macquarie and Chatham Islands. They are music to the ears of nature lovers, adventurers and birders alike. Apart from the

Chathams, these islands are probably more isolated now than they were when they were discovered in the late 1700s and early 1800s and were regularly visited by sealers, whalers and government steamers searching for castaway sailors. pportunities to visit these islands are rare. This expedition is one of rare opportunities to explore all of these islands. Click HERE for the Heritage expedition log Click HERE for the Heritage slideshow of the voyage Click HERE for bird species list |

|

|

Dec. 5th - Snares Island

Our first stop aboard the Heritage Adventurer

Snares islands lie 105 km south-southwest of Stewart Island, and were originally named simply ‘The Snares’ by Captain George Vancouver when he discovered them in November 1791. Vancouver considered the islands to be a hazard to shipping, hence the sinister name. The two main islands are covered with tree-daisy forest and tussock grassland. As the islands have never had introduced mammals establish, the wildlife is both abundant and approachable. Perhaps the most well-known bird species on the islands is the Snares crested penguin. As its name suggests, it breeds only within the Snares Islands, where it breeds on the two main islands (North East Island and Broughton Island), plus on two islets of the Western Chain, 5 km to the south-west. |

|

Dec. 6th - Auckland Islands, Enderby Island

We landed by Zodiac at Sandy Bay to begin a long treck through mud and tussaks along the east coast to Derry Casle Reef. Along the way we detoured into the rata forest for a luch break, and had good opportunities to photograph endemic Auckland Island shags and yellow-eyed penguins along the northern cliffs. From the Reef, a walk over open land above the cliffs brought us th the boardwalk that cuts directly across the island back to Sandy Bay. |

|

Sub-Antarctic megaherbs

|

Dec. 8,9th - Macquarie Island

Macquarie island lies about half way between New Zealand and Antarctica, and marked the southernmost extent of our voyage. The island has been awarded World Heritage status, largely largely due to its unique geology. as one of the few places on earth where mid-ocean crustal rocks are exposed at the surface due to the collision of the Australian and Pacific Plates. Moreover, Macquarie is home to to four species of penguin, Kings, Royals, Gentoo and Rockhopper. The Royal Penguin occurs nowhere else in the world.Frederick Hasselborough discovered the uninhabited island in 1810 while looking for new sealing grounds, and for the next hundred years seals, and then penguins, were hunted for their oil almost to the point of extinction. The sealers also introduced various animals including rats, mice, cats and rabbits. The native bird population was virtually eliminated and plants destroyed. The Tasmanian National Parks and Wildlife Service which administered the island recently embarked on a very ambitious eradication program which appears to have been successful. The island is now predator free and both the birds and plants are responding.

|

|

Royal and king penguins at Sandy Bay

The royal penguin colony above Sandy Bay

A boardwalk leads up from the beach to the colony. The penguins get there by following a stream.

Royal penguin colony; Sandy Bay, Macquarie Island Royal penguin colony; Sandy Bay, Macquarie Island High resolution panorama - download and zoom in to count the penguins... |

Pairs of royal penguins can be very affectionate with one another, displaying mutual grooming and other gestures. However, in the dense colony the penguins fiercely guard their personal space. Any intruder who tries to nonchanantly barge through the throng faces voiciferous opprobrium, and maybe a hard nip from a beak.

Cruising past the king penguin colony at Lucitania Bay

King penguin colony with penguin 'digesters' used to boil them down for oil; Lusitania Bay, Macquarie Island King penguin colony with penguin 'digesters' used to boil them down for oil; Lusitania Bay, Macquarie Island |

Dec. 11th - Campbell Island

Campbell Island / Motu Ihupuku is an uninhabited subantarctic island of New Zealand. It is a UNESCO World Heritage Site, and the closest piece of land to the antipodal point of Ireland, meaning that the furthest away city is Limerick, Ireland. Campbell Island was discovered in 1810 by Captain Frederick Hasselborough of the sealing brig Perseverance, and named for the shipowner Robert Campbell. it too was soon occupied by sealers who introduced rats and cats which have since been eradicated. The vegetation which the great English botanist, Sir Joseph Hooker described in 1841 as having a “Flora display second to none outside the tropics” is now flourishing and is nothing short of spectacular. |

Our visit to Campbell Island began with a morning Zodiac cruise along the cliffs and rocky coastline.

The Campbell island teal was long thought to have been driven to extinction when rats were introduced to the island. In 1975 it was rediscovered on a small islet near Campbell that had remained rat-free. The population was so small that a single event could have driven it to complete extinction To prevent this from happening, 11 individuals were taken into captivity. Captive breeding was initially very difficult to achieve, but uccess came in 1994 when Daisy, the only wild origin female to ever lay eggs in captivity, finally accepted a mate. Subsequently, breeding has occurred every year. In the final phase of the ecological restoration of Campbell Island the world's largest rat eradication campaign was undertaken in 2001. Fifty Campbell teal were reintroduced to Campbell Island in 2004, and after an absence of more than a century the birds are now thriving in their ancestral homeland.. |

After returning to the Heritage Adventurer for lunch lunch in we headed back to the island by Zodiac, landing at the old meterological station. This was replaced by an automated weather station, but the buildings later served as a base for the rat eradication program.

A boardwalk ascends from the met station to the Mt Lyall col, initially through dense raita forest then emerging onto open tussak grassland where the royal albatrosses nest.

Dec. 13th - The Antipodes Islands

A full day's sailing from Campbell Island brought us to the Antipodes Islands, a group of inhospitable and uninhabited volcanic islands in subantarctic waters to the south of – and territorially part of – New Zealand. The name derives because they are almost opposite to London on the planet. As a World Heritage site landings are not permitted, and we Zodiac cruised to view the wildlife on the shores. We were lucky to have fine, sunny weather, and I was pleased to get good photographs of erect crested penguins and northern rockhopper penguins; numbers 15 and 16 on our list of penguin species observed and photographed in the wild. Three more species to go! |

A wonderful day at the Antipodes Islands in good weather. A chance to photograph two new species (for us) of penguins. Erect-crested penguins breed only on the remote and infrequently visited Antipodes and Bounty islands. As the name implies, their most obvious defining characteristic is their pair of erect yellow crest feathers; quite different from the other crested penguin species. Rockhopper penguins were traditionally classified as a single species but were split into three distinct subspecies in 1992; the southern, (E. c. chrysocome), eastern (E. c. filholi) and northern rockhopper penguin (E. c. moseleyi). The three subspecies are distinguished by differences in the length of the tassels of the crests, the size and colour of the fleshy margin of the gape, colour pattern on the underside of the flipper and differences in the size of the superciliary stripe in front of the eye. Proof that the three subspecies were truly different, in terms of more than reproductive isolation and some morphological features, was found in the mitochondrial sequences of the three species. |

Dec. 14th - Bounty Islands

The Bounty Islands are a small group of 13 uninhabited granite islets and numerous rocksin the South Pacific Ocean. Territorially part of New Zealand, they lie about 400 miles east-south-east of New Zealand's South Island and about 100 miles north of the Antipodes. Captain William Bligh discovered the Bounty Islands en route from Spithead to Tahiti in 1788, and named them after his ship HMS Bounty, just months before the famous mutiny. |

|

Dec. 15th - Pyramid Rock and South East Chatham Island.

Pyramid Rock stands isolated in the ocean, to the south of the remote Chatham Island group. It is not possible to land on the rock, and instead we made two circumnavigations in opposite directions aboard the Heritage Adventurer. The rock is the only known breeding colony of Chatham Albatross. |

South East Chatham Islands

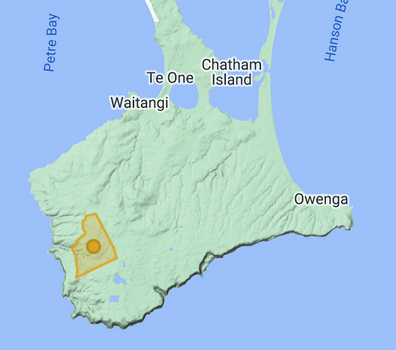

Dec 16th - Chatham Island; Waitangi and Tuku Nature reserve

Chatham Island is by far the largest island of the Chatham Islands group, in the south Pacific Ocean off the eastern coast of New Zealand's South Island. It is said to be "halfway between the equator and the pole, and right on the International Date Line", though the point (180°, 45°S) in fact lies ca. 173 miles WSW of the island's westernmost point. The island is called Rekohu ("misty skies") in Moriori, and Wharekauri in Māori. The island was named after the survey ship HMS Chatham which was the first European ship to locate the island in 1791. |

|

We transferred from the Heritage Adventurer by Zodiac to the jetty at Waitangi, and then had a couple of hours to look round Waitangi, the main port and largest settlement of the Chatham Islands, before boarding a bus to the Tuku Nature Reserve. The small art gallery in Waitangi was closed, but I found much to photograph in the quirky gardens around the gallery. |

A steep and muddy "jungle-gym' hike around the loop trail in the Tuku Nature Reserve.

The Tuku Nature Reserve is a nature reserve on Chatham Island, New Zealand, in the Tuku-a-tamatea (Tuku) River Valley in the south-west of the island. The 1238 hectares of land, largely covered with dense native forest, are owned by the New Zealand government and is managed by its Department of Conservation The reserve comprises an area of forested, peat-covered tableland dissected by the Tuku River and its tributaries and dominated by tarahinau. The valley also contains kopi, karamu, hoho and matipo, with abundant tree ferns. As well as the tāiko, the reserve is important for the conservation of other animals and plants endemic to the Chatham Islands, such as the parea or Chatham Islands pigeon. [Wikipedia] |

|

|

Nov 13th

A few photos copied over from my UCI Campus website

Sunday morning at Bolsa Chica: Nov. 6th.

Trying out my new Canon R7 wth the help of a reddish egret

Eastern Sierras Fall Colors: Oct 22-24.

Scenics

Trees

Just leaves

Benton Hot Springs: Oct 22-24.

Ikebana: Oct 29.

Anne has started a class on Ikebana (Japanese flower arranging). Look for a new arrangement here each week.

The Curious Columns at Lake Crowley: Oct. 22

After California’s Crowley Lake reservoir was completed in 1941, strange column-like formations were spotted on the eastern shore. They had been buried and hidden for eons until the reservoir’s pounding waves began carving out the softer material at the base of cliffs of pumice and ash. The rising gray and stony cylinders have cracks ringing around them at intervals of about 1 foot and have inspired comparisons to Moorish temples. Many are gray, straight as telephone poles and encircled with horizontal cracks about 12 inches apart. Some are reddish-orange in color. Some are bent, or all tilting at the same angle. Still others are half-buried and resemble the fossilized backbones of dinosaurs.

To investigate their origin, geologists at UC Berkeley used a slew of different methods and equipment, including X-ray analysis and electron microscopes. The researchers hypothesize that the columns were created by cold water percolating down into — and steam rising up out of — hot volcanic ash spewed by a cataclysmic explosion 760,000 years ago. The blast, 2,000 times larger than the 1980 eruption of Mt. St. Helens, created the Long Valley Caldera, a massive 10-by-2-mile sink that includes the Mammoth Lakes area. It also covered much of the eastern Sierra Nevada range with a coarse volcanic tuff, or ash fall. The columns began forming as snowmelt seeped into the still-hot tuff. The water boiled, creating evenly spaced convection cells similar to heat pipes. Tiny spaces in these convection pipes were cemented into place by erosion-resistant minerals. [LA Times article]

The columns are usually submerged during the summer, when the water level in the reservoir is high. Good directions for how to find them are here.

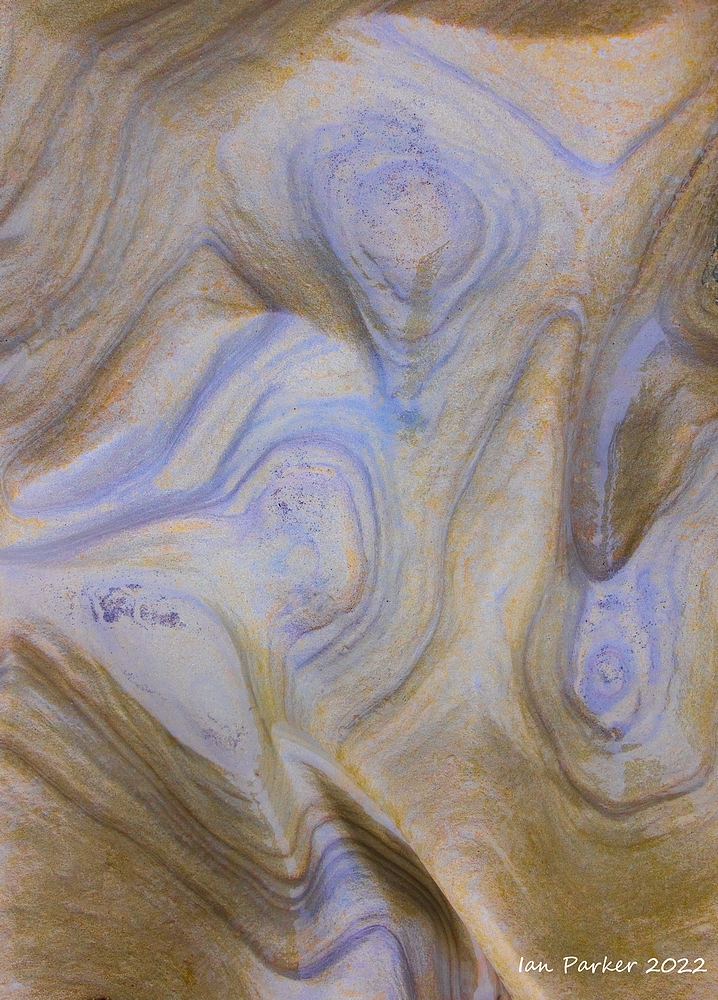

A week at the John C. Campbell Folk School: Oct. 3-8

Anne and I spent a week at the John C. Campbell Folk School in the Appalachian mountains of North Carolina. Anne studied and practiced the 'Science of Breadmaking' (with delicious results), while I took the photos here during my class on 'Photography for the Zen of it'. The Folk School is spread across a bucolic campus of woodlands and open fields that made a serene environment to escape from the world for a week. My photos here were taken largely on the School campus, and I have arranged them rougly in a sequence beginning from 'straight' shots of landscape and buildings to increasingly 'Zen-like' compositions and abstractions.

| |

| |

An excursion to Utah and Nevada: Sept. 17-21

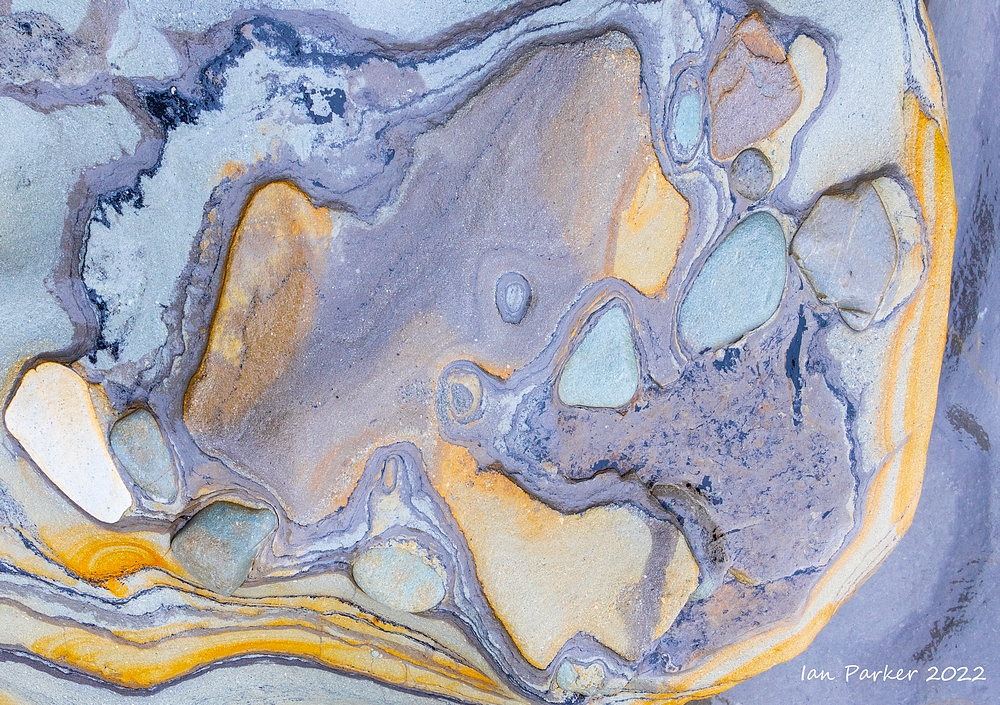

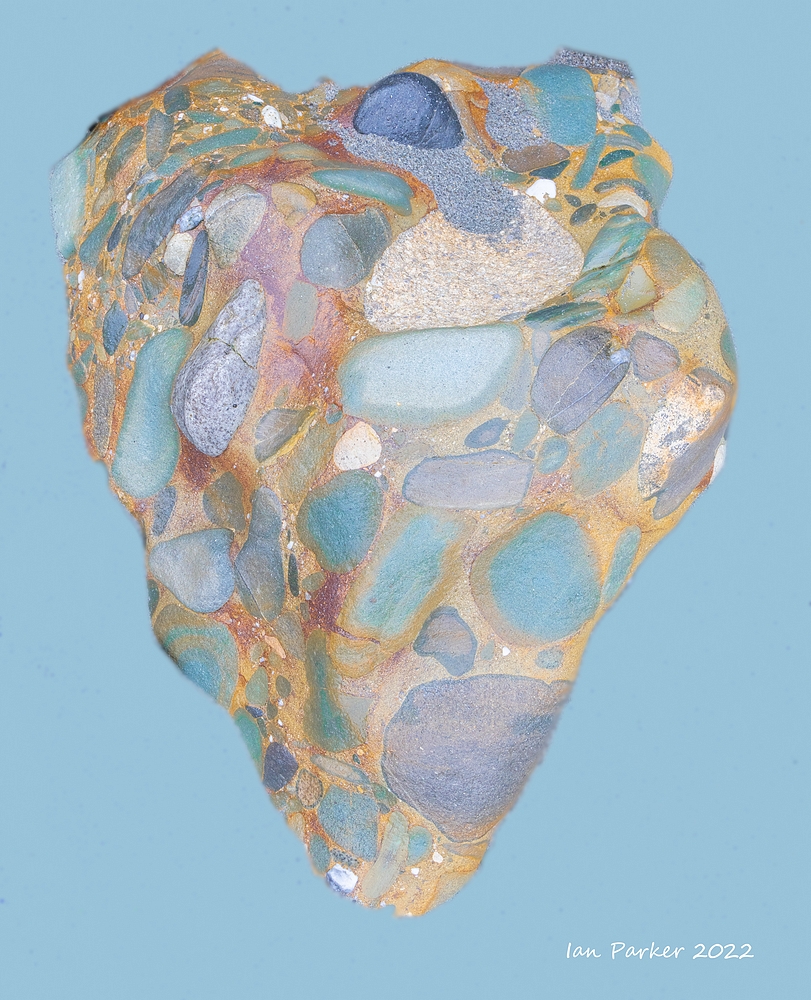

An overnight stop at Color Rock Quarry to break the long drive to Utah.

Continuing into Utah, we were too early for fall colors, even at the highest elevations at Cedar Breaks and Boulder Mountain, but found a single grove of yellow aspens by a lava flow with complementary lichen on the rocks..

A stop for the night along Cainville Wash

And our last destination, exploring the remote region of Yellow Cat Flat at the 'back' of Arches National Park.

Bolsa Chica: Sept. 4

Trying to escape the heatwave by going down to the coast - but still hot at Bolsa Chica at 7:00 am.

BADWATER 2022, July 11-13

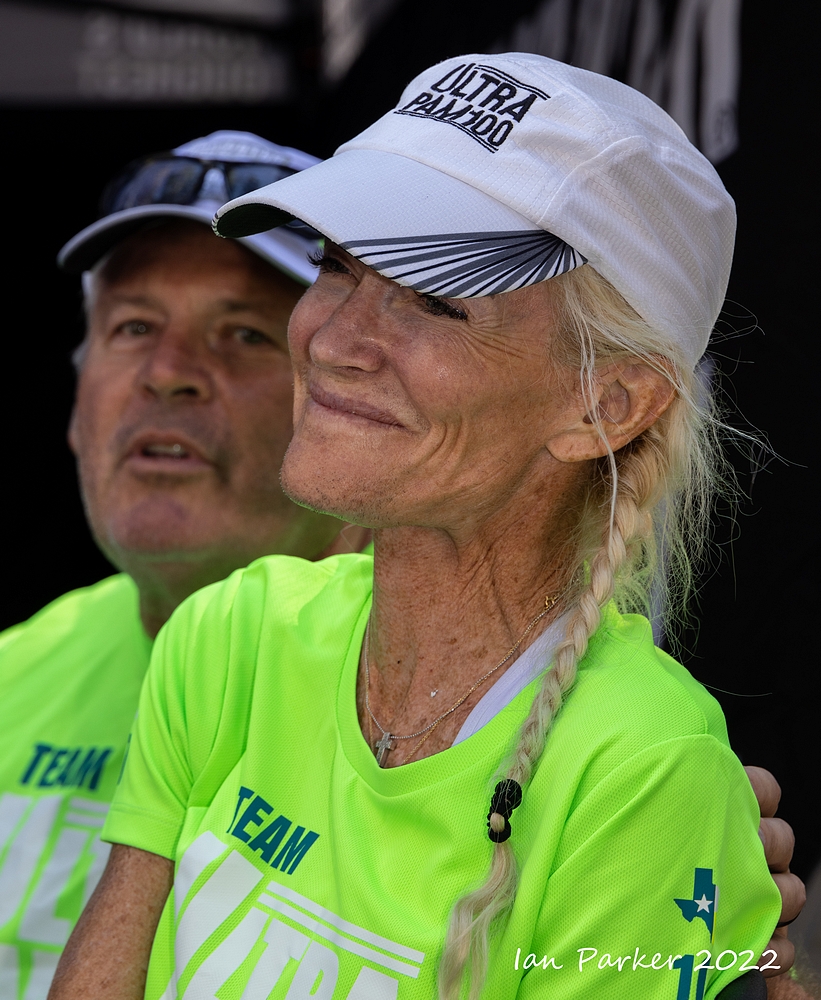

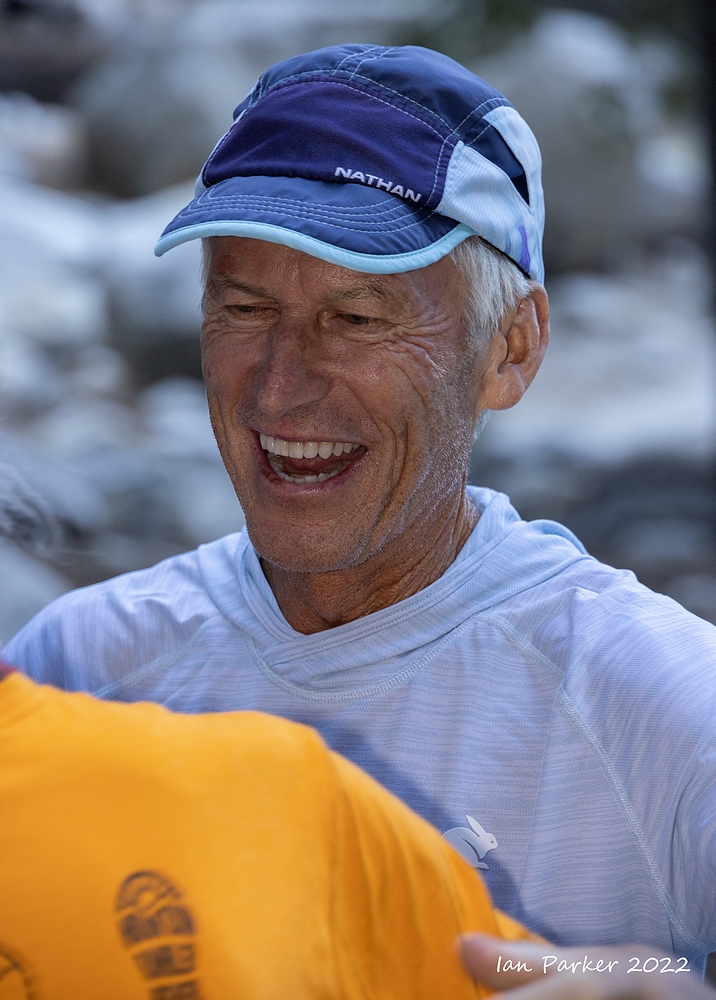

This was my 17th year at the Badwater Ultramarathon, the "World's toughest footrace"; eleven years as a runner or pacer, and six helping on the race staff and as a photographer. My approach the first year I came to photograph the race was from the perspective of a landscape photographer, aiming to place the runners in context of the spectacular scenery of Death Valley and the Eastern Sierras. This year I shifted gears, and also took on the mindset of a 'street'/portrait photographer, concentrating on the runners and their support crews. Badwater offers a photographic challenge of capturing the emotions of a group of very special people pushing themselves to the limit in an extreme environment.

The images below are a selection from many hundreds of shots. Click HERE for the race website which includes links to many ofther photos and full race results.

Start line at Badwater Basin for the 8:00pm wave

Start line at Badwater Basin for the 9:30pm wave

Runners on the ramp from the boardwalk

I took a few hour's sleep and caught up with the runners at dawn, when they had already covered 35 miles through the night

The 5000ft climb up Towne Pass

A welcome break and some shade at the 'Oasis', safely past the 50 mile cutoff; then up to the summit of Towne Pass

Descent from Towne Pass into Panamint Valley

Through the time station at Panamint Springs, up the steep and winding ascent to Father Crowley Lookout, and on over the summit to finally leave Death Valley National Park at mile 84.

I got a few hours sleep while the runners continued on through their second night, and caught up with them at dawn on the descent to Owens Valley

The Whitnay Portal Road

- maybe the World's toughest half marathon with 4500ft ascent coming after 122 miles

After 135 miles, the Finish Line

June 12-24 A visit to Iceland - Mostly for the birds.

Denver - Keflavik on Iceland Air

TSA lines at Denver were long but moving fast

A window seat to Keflavik

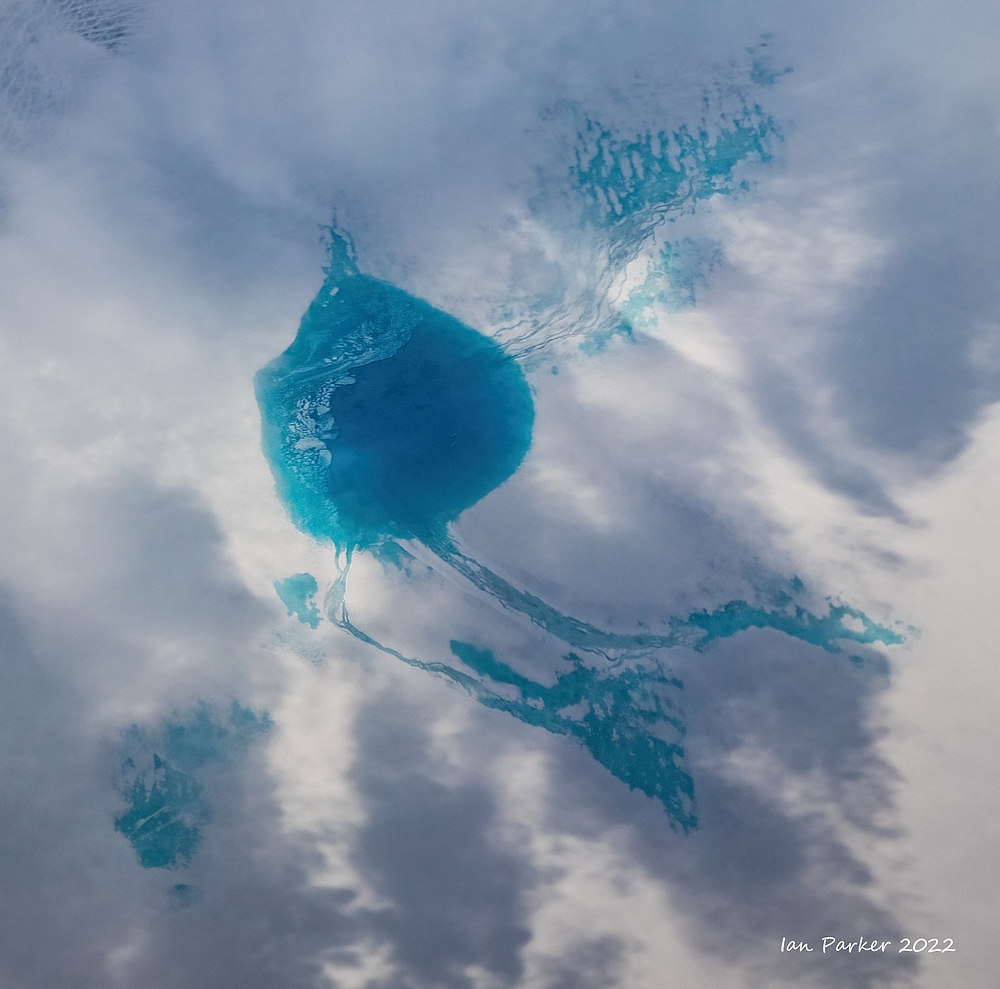

Crossing over the tip of Greenland on the way home

A jet-lagged early morning wander around Reykjavik

Landscapes and villages in east and south Iceland

Sea cliff waterfall; Iceland |

| |

Basalt columns in Stuðlagil Canyon

Jökulsárlón glacial lagoon and the Diamond Beach

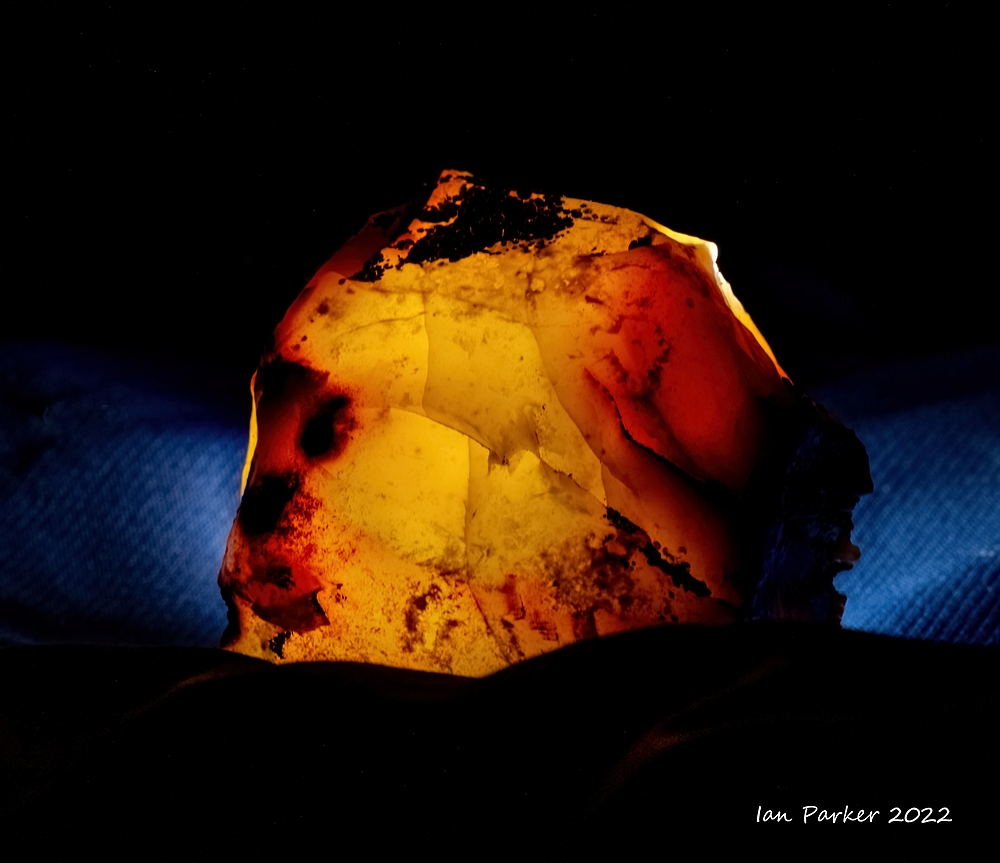

An early morning stop at Jökulsárlón driving back to Keflavik. The sky was heavily overcast, with light rain. I was not finding inspiration for wide landscape photography at the Diamond Beach, but the rain polished some almost transparent bergs revealing an intricate inner landscape within the ice.

Eider ducks among the icebergs in Jökulsárlón

glacial lagoon

Scenes and birds in Northern Iceland

Whooper swans by the ring road

Gannet colony on a sea stack at Rauðinúpur Cape - the extreme north-eastern tip of Iceland

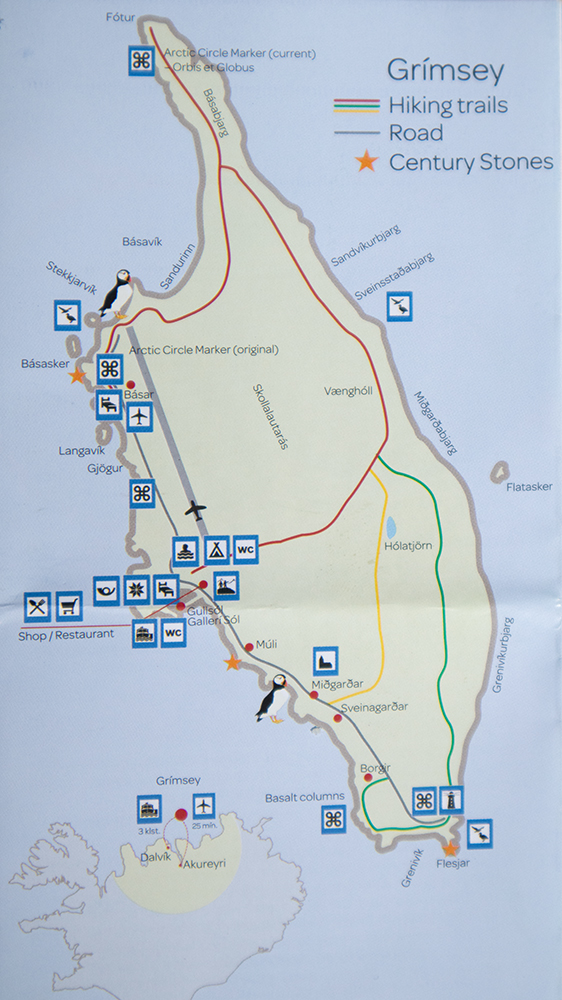

Three nights on Grímsey Island

Grímsey is an island off the north coast of Iceland, nestled across the Arctic Circle. It is, therefore, the only part of Iceland that is truly in the Arctic. There is a famous monument marking the edge of the Arctic Circle: an eight-tonne sphere of stone. The shape was designed to represent the rolling movements of the true Arctic circle, as a rooted monument would not be able to move along with its true location. (As a side note, the boulder may soon have to enter the seas to the north, as the Arctic Circle is moving away from Grímsey. It is expected that by the middle of the 20th Century, it will no longer be considered Arctic territory.)The island’s biggest attraction is its wealth of birdlife; millions from dozens of species make Grímsey their home.Their numbers are so prevalent here for several reasons. First, the arctic seas around the island have plenty of fish, meaning the birds have plenty to eat. Secondly, hunting the birds and the collection of eggs have also been minimised in the last half century (although the traditions do still continue.Finally, there are no mice, mink or rats, meaning the eggs can lay safely in the low grass.The main attraction for me is Atlantic Puffins that nest on the island, but there are wide range of other species, including Black-Legged Kittiwakes, Auks, Razorbills, Thick-Billed Murre and Northern Fulmar. ..The best season for birdwatchers to visit Grímsey is between May and September. Outside of the warmest months, the birds migrate to warmer climates. Also, June brings 24 hr daylight, with the sun never setting around the summer solstice.Click HERE for an evocative video about Grimsey by Einar Guðmann and Gyða Henningsdóttir. |

Grimsey scenics

For the elves; Grimsey |

Bouncy mat; Grimsey |

Puffins

Puffins under a midnight sun

Shooting puffins into the light reflected by waves from the midnight sun created a background of 'bokeh balls'.

Razorbills

Gulls

Birds in the village pond, Grimsey

Red-necked phalarope

Arctic terns

Birds in the grasslands

Icelandic sheep

Earlier photos from this year are HERE

| IanParker 1146 McGaugh Hall University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 |

Please send enquiries to |

BACK TO > |

Kawai

Kawai

.jpg)

.jpg)